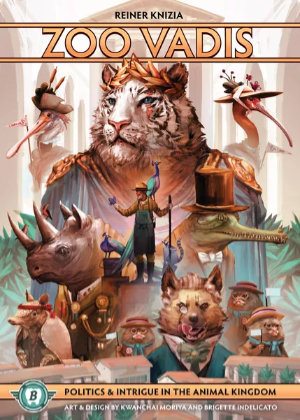

Zoo Vadis Board Game Review

By MARK WILSON

Year Published: 1992/2023

Players: 3-7

Playing Time: 20-45 Minutes

Designer Reiner Knizia doesn’t lack for prolific output, and there basically isn’t a genre of board game that he hasn’t touched. However, negotiation games are one that he hasn’t dabbled in much, at least relative to his usual mechanical playthings like pushing your luck with dice rolls or numbered cards, tile laying, and hand management card games.

Oh, sure, many of his games feature enough interaction that an implicit negotiation space exists on top of the game, in the realm of trying to convince your friends that, in fact, someone else is winning and needs to be stopped. But these aren’t explicit in many of his rule sets. Zoo Vadis is an exception.

Zoo Vadis – The Premise

The animals have taken over the zoo, and left only one human alive. This isn’t the actual story we’re told, but it’s also left open to some interpretation, and so it’s my dark head canon.

They’re forming hierarchies, and all the major animals want to be the zoo’s new mascot. So they’re in a political climb to the zoo’s Star Exhibit while also trying to curry the most credit in the form of laurels that act as the game’s currency.

You’ll be placing animals on the game board, then maneuvering them up through a series of locations toward the star exhibit. Very little can be done unilaterally, so you’ll need to work together with other animals to make progress. After all, no election was ever won without gaining favor from numerous different demographics. And so you’ll find yourself asking for votes in exchange for favors, bribing others for those same votes, and extracting value for your support of their efforts.

Deals made that can be enacted immediately are binding. Future promises are not, though. This invites backstabbing, but also threatens the backstabber with the consequences of their actions, which might be that the entire table stops playing nice with them.

In a fun inversion of normal gaming heuristics, the animal with the most laurels wins the game, but only if you manage to get one of your animals into the star exhibit. This isn’t easy, and often requires that you make bribes and pay favors to others in order to get into the exhibit before it’s full.

All of the laurels in the world mean nothing if you’re on the outside looking in at the exhibit. These two goals help to frame the game’s trades, negotiations, and strategic considerations.

Lineage, Looks, and Modern Tendencies

Zoo Vadis resurrects a pretty pure negotiation game of Knizia’s, 1992’s Quo Vadis. The latter is about Roman senators vying for influence and rulership, and so the political theming worked a bit better than it does here. Zoo Vadis, however, makes every attempt to recreate a more primal, metaphoric version of the Roman senate, and succeeds admirably enough in this regard.

Quo Vadis is, in the modern hobby, perhaps dragged across too many coals for its rather spartan aesthetic. To my eye, it’s actually the cleaner of the two from a usability perspective. But bright colors, anthropomorphic animals and visual density are the name of the game here in the 2020s, and Zoo Vadis reflects this.

So, too, are its additions. Heaven forbid we remove anything from a game to more quickly get to its core tensions. No, “more is more” is the mantra of The New. The consumerist forces demanding we agree to this are too mammoth for me to fight in the mere words of my review, so I’ll merely say that this is true of broad modern hobby game preferences, but should not be seen as a truism for all.

Fear not, though; my criticism just above is a general one, but juxtaposes nicely with Zoo Vadis as an exception.

The game’s additions include the presence of a new mechanic in some peacocks that strut around the board. They have no desire to be the zoo’s mascot, but they’re vain and greedy, and can be bribed to help you along your way. They can also be used to clog up the star exhibit, blocking others from entry.

The other addition is in the form of (optional) abilities unique to each animal type. But in another novel inversion, these abilities can’t be used on the animal who wields them. Rather, they can only be used for the benefit of other animals.

As such, the special abilities become new bargaining chips, and their price must be appropriately set in order to make their use mutually beneficial.

The Beauty of Constraint

I’ve hedged so far on piling on praise, but Zoo Vadis deserves a lot of it. The “more is more” mentality that I mention, which is usually a red flag for me, here becomes a positive, because the additions are carefully managed to add interpersonal and tactical nuance without bloating the game’s length or rules overhead.

Speaking of length. The game plays in around 45 minutes, and – believe me when I say this – it will be over before you’re ready. Many are the players I’ve seen who have grand plans to reap the benefits of their board positioning…until the game races to its conclusion (the star exhibit filling) and they’re left in the cold, possessing only their failed plans and a handful of useless laurels.

This has the effect of leaving you wanting more, rather than overstaying its welcome. It’s the far better problem to have.

Mind you, one of the few criticisms I may have of Zoo Vadis is that another 20 minutes or so of gameplay might produce more satisfying narrative arcs. But the race to the end as-is gives the game its own wonderfully kinetic energy that might be lost with additional length.

And like so many other Knizia games, here there are only four possible actions to learn, but loads of emergent considerations that invariably affect and involve other players. It’s the correct type of constraint, not to the decision space but in the cognitive overhead required before you get to the interesting decisions themselves.

Bounded and Freeform Negotiations

Like one of my favorite negotiation games, Bohnanza, another useful constraint is that you can only negotiate with the active player. For a game that holds up to seven players, not having freeform negotiations is a boon, because this would intimidate many people away from the game. In this form, it’s more approachable for those to whom direct negotiations can be difficult to navigate.

But you can haggle with any player on their turn, and so you’re never far from the action.

Outside of that constraint, though, very little is off-limits within the game’s structure.

And much like other negotiation classics, the action is extremely player-driven. Cries of one animal ability or another being overpowered dot discussion forums, for instance, but this is categorically not true, because every power can be negotiated for its presumed worth. If a particular animal keeps winning, it’s not a sign that that animal is too overpowered, but that the table’s collective understanding of relative value needs to shift.

Similarly, since animal abilities are situational, if one player never has a chance to use their ability (I’ve seen players win without a single use, for reference), then it behooves everyone to shift their bargaining to reign in whoever has had better situational luck.

Thus there’s a pendulum that swings back and forth in each game, and it’s informed not just by who’s doing well or poorly, but by what you personally need on your turn. Align your interests with enough others throughout the game and you’re likely to succeed. Try to work alone or actively hinder others too much, and you’ll find your climb to the star exhibit to be slow and laborious.

Theme and General Appeal

That description above sounds a lot like politics, doesn’t it? The theme is thus brought to life not via the aesthetic trappings of the zoo (which, my earlier quibbles aside, is lovingly and beautifully rendered), but via the gameplay itself.

And in another hallmark of many of Knizia’s best games, it’s sometimes shockingly thematic because of how the theme manifests organically and doesn’t feel forced.

Negotiation games are, by their very nature, socially demanding. So this will limit the audience somewhat. You can also win without backstabbing, and often it’s easier to do so. But the possibility of these nefarious elements remains, and particularly in the game’s final stages it’s often advantageous to take advantage of promised favors in small ways (or large ones!). The game is over too quickly for this to leave a bad taste in my mouth, but plenty of gamers run screaming from such punitive aspects of play.

I run toward them, because within the shared social circle of the game, there’s no actual animosity or ill will. The most brutal beats – to myself or others – produce the hardiest laughter in those who seem to love the game. Embrace this as part of the fun, and it’s a lovely little romp.

And to throw a bone to the publisher, Bitewing Games, who was pleasantly transparent about the zoo theme and how it’s tied to financials and modern preferences and still aimed to retain the core spirit of the game (which it does), I have to admit that the box art alone has convinced some to play this with me, and that they’ve generally enjoyed themselves even if they know nothing else.

So even if I roll my eyes a bit personally at how an anthropomorphic animal retheme is all that’s required to sell some additional copies and garner more interest, I can’t deny its effectiveness, and I’m grateful for anything that allows me to play this gem as much as possible.

…

Like my content and want more? Check out my other reviews and game musings!

Read More From Bumbling Through Dungeons

Recent Posts

Categories

- All (354)

- Announcements (4)

- Board Games (206)

- DMing (28)

- Game Design (16)

- Playing TTRPGs (22)

- Reviews (192)

- RPGs (142)

- Session Reports (91)

- Why Games Matter (9)