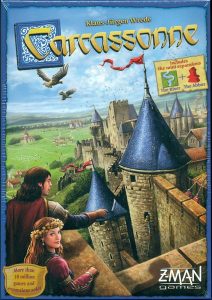

Carcassonne Board Game Review

By MARK WILSON

Year Published: 2000

Players: 2-5

Playing Time: 30-45 Minutes

Carcassonne – The Premise

You draw a tile, then place the tile in a way that matches geographically with the tiles around it (roads connect, etc.). Then, optionally, you place one of your meeples on the tile, on one of its elements (field, road, city, etc.). You have a limited number of meeples to play, but can get most of them back by closing off a road, city, or surrounding particular tiles. Scoring is based on how efficiently you were able to place and retrieve your meeples, and occasionally on who has the most meeples in a particular connecting field.

You probably don’t need me to explain Carcassonne, but plenty of resources exist if you’re truly unfamiliar with it. It’s simple. Or is it?

The Components

This is a little tricky to discuss, because there are, hell, probably dozens of editions and variants at this point. In general, though, the tile art is pastoral and pleasantly functional, which will please some and bore others.

Why Do a Review of Carcassonne?

When I’m covering juggernauts of the hobby, I always ask myself what I’m bringing to a review that hasn’t been done before. Most likely, the answer is “not much.” Hopefully, however, there are a few things. Among my goals:

- Remind people just how good this game is.

- Posit the opinion that it’s the best of the turn-of-the-century gateway games that have become the ubiquitous standard bearers of modern gaming.

Is It Strategic, Tactical, Both or Neither?

A usually introductory critique of this game is that it’s quite random. And it’s at least partially true, because there will be games where you need one type of tile, and your next 8-10 pulls won’t produce it, while your opponents will benefit from some great luck.

This is overly reductive, though, because part of the strategy is adapting to the tiles you draw. I don’t want to make this a strategy article (I’m not good enough at the game for that), but I make this point because I want to talk about the subtle nuance of Carcassonne.

For example, when do you place your first meeple in a field? And which field? And how do you go about subsequent field placements? It seems arbitrary at first. It’s going to vary, but a holistic analysis of the ever-expanding play area will often yield opportunities to capitalize on field placement that you would miss if you’re only focused on the best place to situate the most recent tile you’ve drawn. It lends a subtle, longer-term strategic angle to a game that can initially feel random at worst, and turn-to-turn tactical at best.

Carcassonne is filled with such subtleties. My favorite is when I see someone add to someone else’s city, without entering it themselves, in order to make it all but impossible to close it off before game’s end. How many games reward taking a turn where you give your opponent an extra point while simultaneously gaining zero points yourself? Magical.

Others will still level this criticism at Carcassonne, and the variance of tile draws does play a big role in things, so it’s not entirely unwarranted. To me, though, neither is it terribly damning.

This is also why the popular three-tile variant exists, which sees each player with three tiles in their hand to choose from, rather than only drawing one on their turn. I like this variant, but have never felt like it’s needed.

The Pantheon of Modern Board Gaming

If I’m creating a Mt. Rushmore of games that spurred the modern board gaming Renaissance, Carcassonne is undoubtedly on that list. Or, to state it in a less geographically specific way, it’s among the 3-5 games that are most responsible for modern gaming being what it is today.

This is a somewhat subjective statement, and if your own list includes 3-5 without Carc, I won’t argue. But it’s in that conversation, and is going to be on most peoples’ lists of most influential modern games, along with games like Catan, Ticket to Ride (TTR), Pandemic and a handful of others.

I’d posit that games like Ticket and Pandemic have been surpassed for many gamers, oftentimes within their own gaming family. Many will graduate from TTR, for example, but may still enjoy its many descendants (Europe, Nordic Countries, UK, etc.) that add various mechanics to deepen the experience.

Same with Pandemic, which has a whole family of games in varying genres, and arguably perfected the legacy game with its Pandemic: Legacy series. Catan is a bit of an outlier, but I don’t know a ton of regular gamers who continue to pull it for more than nostalgic reasons.

Which makes Carcassonne a bit of an outlier. Even without one of its myriad expansions, the pace and mechanics don’t seem any more dull to those I’ve spoken with than when they first played the game. This is, admittedly, wildly anecdotal. But in a recent list of the most played games in BGG’s history, Carcassonne was one of the most consistent over nearly two decades of gaming. Gamers haven’t moved past it, which is somewhat shocking given the influx of gamers in the last decade and the industry’s tendency toward the shiny and new.

Expansions Galore

One possible reason for this continued popularity is that while TTR and Pandemic iterated with entirely new games, Carcassonne has instead released numerous expansions that add to the base game.

I won’t go into them here in any depth, except to say that most add new tile types and – usually – new ways to score, which gives you more to consider. Common wisdom seems to suggest that you should find one or two expansions that you like and stick to those, because there’s eventually some diminishing returns on continually adding expansions. I can attest to this, and frankly like the game about same with no expansions, the first expansion, the second, or both first and second together. I’ve only played sporadically with others (not enough to write about them or even remember them too well), but having read through how they work, none stand out to me as being more game-changing than most others.

Who Won’t Like This

It’s simple enough that, despite the nuance I referenced, some will tire of it. I’d suggest that expansions or the three-tile variant might shake this up a bit, but also won’t try to sell a game to someone not enamored with the premise. The theme is also…light? It’s not that it’s pasted on; the buildings, scoring types and artwork work well together, but it’s also just not very present. There’s nothing wrong with feeling like you’re playing a tile-laying, worker placement game rather than building cities and roads in rural France, but if you’re looking for the latter, this isn’t it.

Carcassonne – Conclusions

I see a common thread running through some games – even those in different genres – where you literally only have 2-3 rules to remember, but have plenty to think about on a turn, and without your options being overwhelming. Dixit (another game I’ve reviewed) is like this. So is Carcassonne. And that gives it a timeless quality, because any variation of it will invariably mess with the elegance of the original. There’s a satisfaction in that style of game, and I feel it intensely upon playing Carc.

I would stop short of ever saying that certain games need to be experienced by modern gamers. There’s no such thing as a “required” game. But if I’m recommending games that represent elements of the modern hobby, Carcassonne is still at the top of the list. It’s not a transcendent experience like my favorite games, but is also one that I’m always delighted to come back to. I didn’t play this until I was well into the hobby, so this isn’t even nostalgia talking. I’m just glad I circled back to discover it long after I had played several of its thematic descendants.

…

For more content, or just to chat, find me on Twitter @BTDungeons, and if you enjoy my work, be sure to subscribe on Youtube!

Share

Recent Posts

Categories

- All (356)

- Announcements (4)

- Board Games (207)

- DMing (28)

- Game Design (17)

- Playing TTRPGs (22)

- Reviews (193)

- RPGs (142)

- Session Reports (91)

- Why Games Matter (9)