High Society Board Game Review

By MARK WILSON

Year Published: 1995

Players: 3-5

Playing Time: 15-30 Minutes

I didn’t think I needed another auction game. Designer Reiner Knizia’s so-called “Auction Trilogy” from the 90s features Medici, Modern Art and Ra. 1994’s High Society doesn’t even make the cut, apparently.

I guess the world just loves artificial trilogies.

What I found in High Society is a game that gives each of those others – legends in their own right – a run for their money. When accounting for the time to teach and play, I’m not convinced that High Society isn’t the best of the whole bunch.

The Delusion of Labels

I actually understand why it might not be included. It comes in a box that might get lost in a crack in the floor. It teaches in five minutes and plays in 30 even at its highest player count.

And so it’s a “filler.” Which, in the minds of too many board gaming diehards, is the equivalent of “worse.” It’s lesser in some nebulous way.

Except it’s not.

Nevermind that the other three I mentioned teach fairly quickly too, and will usually play in under an hour. They seem weightier and more strategic on the surface, and so they get an outsized amount of attention. And that doesn’t include comparisons to even meatier games that will add entire rules systems atop the central auction, and will take as long to teach and set up as High Society does to play. Those are “real” games, not this childish 30-minute pablum.

But I own Modern Art and have easy access to both of the others, and High Society gets played more than any of them in my circles. Granted, I’m the one introducing it to the table, but no one’s complaining or asking for an alternate option.

High Society – Overview

You’re an elite socialite, trying to prove that yours is the most enviable lifestyle. It’s all quite grand…until you have to pay for all the extravagance.

You want the most points in High Society over a series of auctions, but at game’s end, the first thing you’ll do is check to see who has the least money left. This player is a phony and not deserving of their supposedly influential status.

This player cannot win the game. From all remaining players, you’ll check scores. So you want the most points, but don’t want to overspend for it.

Starting money is predetermined. Auctions cards come in standard varieties (those worth 1-10 points), or non-traditional, like those that halve or double your total. Three cards also exist that are bad, like the aforementioned halving. In these auction rounds, everyone will pay their bid except the person who eventually passes and takes the card into their score pile. These act as reverse-auction, loss-aversion rounds.

The game has a variable end point, when the fourth of four green-backed cards (it may be a different color depending on edition) is revealed, meaning that rarely will you see every card in the already quaint 16-card auction deck before the game ends.

The Beauty of Subverting a Strategy

The auctions seem straightforward during the teach. Get the best cards without spending the most. Simple, right?

Well…

The biggest, but not only, way the game messes with this is through the reverse-auction rounds for negative cards. See, in every session I’ve played, someone will win a couple cards and, knowing that bids tend to subtly increase throughout the game in such games, will sit tight. They’ve decided that their 13 points (or whatever) is enough to potentially win, and they’re content to sit silently the rest of the game.

But then the card appears that halves your score, or reduces it by 5, and you can see the crestfallen look on their face. “Wait,” they think, “I didn’t want to spend any more money!”

And they don’t have to spend any more if they don’t want to. But they’ll be taking those cards, and pretty soon their score will be paltry.

Just as disconcerting is the player who paid a lot to avoid the negative cards, but doesn’t have a single point to show for it. Sure, Suzy and Dan have negative cards, but at least their total score is still positive!

So the game forces the defensive turtles out of their shell, and forces otherwise calm bidders into wildly risky bids just to get into the mix for the win.

In every game I’ve played of High Society, I’ve had some sort of plan in the first couple rounds. It has never once come to pass, meaning that if I win (which I’ve managed once or twice), it’s because I’m reacting organically to the state of the table and the cards that have come out.

It induces the groans that typify the best games, where every choice is agonizing. It’s also a sound that seems to accompany a lot of Reiner Knizia’s games, so it’s no surprise that I’m such a fan of both this idiom in games and the way he brings it to life.

Judging a Box By Its Cover (and Contents)

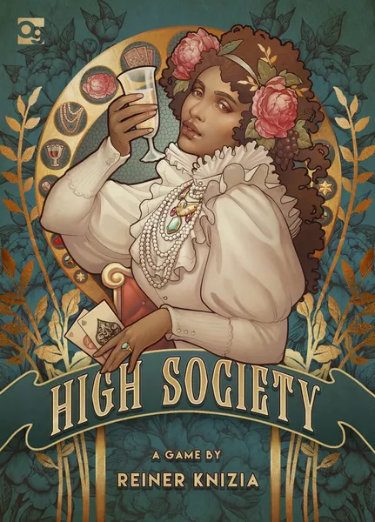

For what amounts to a microgame in its box size, the game oozes theme via its components. The cover art (I own the 2018 Osprey edition, pictured at the start of this article) sets the scene immediately. You can taste the opulence.

The card art is similarly wonderful, painting an evocative picture of the lifestyles you’re simulating through gameplay. Artist Medusa Dollmaker does a spectacular job.

It’s also, to my eye, a subtle parody of that lifestyle and all of the excesses it entails. This could be an abstract card game with nothing but numbers on the cards. Instead, the theme is shockingly well-realized because of how the gameplay subtly mimics the socialite roles you inhabit within the game’s narrative.

It’s a masterclass in art direction for a game, one that heightens the proceedings without making the game itself overproduced or needlessly expensive.

The Length and Width of a Game’s Footprint

Did I mention that this game only takes 30 minutes? If you’re efficient about things, that includes teaching the game.

I compared it to Knizia’s other auction games earlier, and that was deliberate, because I often feel as though this one packs as many interesting decisions and dramatic moments as those games into its shorter playtime.

I enjoy them all to varying extents, make no mistake! Modern Art in particular probably remains my favorite of Reiner’s auction games. I’ve also done (or will be doing) largely positive reviews on each of them as well, at least whenever I work through my queue of hundreds of games I’d like to review. But they’re all good, is the point.

But High Society is the one I play the most, because it packs as much gameplay into it as the others, but in a more digestible format.

As such, it doesn’t feel like a “filler” to me; a game that merely fills a period of time. It packs a heftier narrative punch, to the point where my emotional reaction is equivalent to many longer games.

This is a kind of magic trick, the ability to turn 30 minutes of gameplay into a memory that competes in satisfaction with games two, three or four times longer.

Who Won’t Enjoy High Society?

I once played a session where the game-ending green cards were nearly the first four drawn (and were the first three, so the game could have ended on any subsequent draw). Thankfully we still had a good session, but that luck of the draw can produce some games that are too short for the game to truly come alive.

This is a directly interactive, pseudo-psychological dance as well; those who prefer their interaction to be a touch more mechanical might prefer Ra, also from Knizia. It’s interactive as well, but between its set collection and press-your-luck elements, has more mechanical layers to blunt any interpersonal pettiness that may occur.

I prefer playing the other players directly, so this one speaks more to my preferences (this is true of Modern Art as well), but Ra is inarguably his most popular auction title and is just as likely to be the best option for you or your game group.

High Society – Conclusions

This game has become one of my go-to’s for a specific player count (4-5) and playtime (~30 min.). The fact that I pack it and reach for it more than several others I own and enjoy is about as big an endorsement as I can give it.

The directness of it, combined with the fact that there’s basically nothing mechanical going on outside the auctions themselves, means that some will bounce off of it who don’t enjoy precisely what it’s doing.

But maybe that’s the best word for it: precise. High Society is precise experience, and perfectly catered to the niche it’s attempting to fill. I’d call it no frills, but the thematic frills of the Gatsby-esque parties it implies are enough to muddy that particular description. Regardless, it’s a focused game with absolutely no cruft left on it, even comparing it to other designs from Knizia, a master of removing everything that doesn’t add to the core experience of a game.

So pop the expensive champagne and fire up the yacht; this one’s worth remembering.

…

Like my content and want more? Check out my other reviews and game musings!

Read More From Bumbling Through Dungeons

Recent Posts

Categories

- All (354)

- Announcements (4)

- Board Games (206)

- DMing (28)

- Game Design (16)

- Playing TTRPGs (22)

- Reviews (192)

- RPGs (142)

- Session Reports (91)

- Why Games Matter (9)