Mean Games Don't Exist

By MARK WILSON

I read a take on board gaming that upset me quite a bit recently. I know, I know, reading something upsetting on the internet isn’t anything new. This particular take got to me, though, for a few reasons:

- It was from someone who I otherwise should be aligned with in my love of board gaming and tabletop roleplaying.

- It was stated nonchalantly, as though it were a given truth instead of something that might have a different perspective.

- I’ve seen variations on this opinion before, and it’s becoming more prevalent in gaming discourse.

The opinion, summarized, is that there’s a link between playing games with combative, punitive, or “mean” elements, and being a mean person.

This article exists in unequivocal refutation of that idea, and also to make the point that holding this opinion can be damaging to the very fabric of gaming and what makes it such an amazing endeavor.

The article in which I saw this opinion (most recently) equated a lack of directly antagonistic mechanics in a game with an increase in player compassion, and conflated the two qualities. Moreover, it equated liking heavily contentious games with enjoying the misery of others, or reveling in their failures. It superimposed out-of-game emotion onto in-game actions, basically, and used some extreme examples to paint these gamers in an unflattering light. But that’s jumping ahead a bit. We’ll get there.

I’m not going to link the article, because I don’t want the person to be targeted, and because I think this is a more general issue plaguing certain gaming spaces. Any individual instance of it is merely a symptom.

This is a trend I’ve seen both in-person and in online discourse in recent years, and such a direct version of it was both unsurprising (it’s just saying the implicit stuff out loud that I’ve seen elsewhere) and shocking that it was taken as Truth instead of merely an idea to explore and question.

Consider this article to be the due diligence that was lacking.

The other caveat I’ll provide before beginning is that nothing in this article speaks to gaming preferences, which are personal, subjective, and irrefutable. Love whatever you love, dislike whatever you dislike, and long may your gaming be joyful.

The Magic Circle in Gaming

For any discussion to take place on this topic, we need to define, discuss, and agree upon the role of the Magic Circle in gaming.

The magic circle is a conceptual space where the normal rules of the world are suspended and replaced by those of the adopted, fictional world. In this case, we adopt the premise proposed by the game, and adopt its concepts and rules while detaching ourselves in some conceptual way from our normal lives in order to invest fully in the shared experience of a game.

This is the divide that allows in-game actions to mimic actions we’d never consider out of game. But, suspended within the circle, they don’t carry weight out of the game. So an action that might inspire an antagonistic response if it happened in our everyday lives has no real-world stakes or consequences and can be interpreted only within the adopted game-world. In this way, we can assume roles and take actions without fear of anger or reprisal, as can others who we game with.

Johan Huizinga, a Dutch writer and cultural theorist coined the term in 1939 in a book titled Homo Ludens. Importantly, while he very clearly delineated between these two areas, he didn’t advocate for a complete separation between game-world and real-world, so to speak.

However, this separation is what allows many games to happen, and what allows for joyful experiences to take place without interpersonal vitriol.

Other academics, theorists, designers and gamers have expanded on this central idea, with 2003’s Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals stating that “something magical” truly does happen when the adoption of the magic circle takes place, and it’s thus appropriately named.

The magic circle must be accepted and adopted by players in order for tabletop games to function as a form of entertainment and as a communal, shared activity. It is the basis for any multiplayer game, and our interactions fall apart if it is not accepted.

It takes a level of maturity to fully adopt the circle, perhaps more so in intense, interactive games, but learning to do so is a prerequisite to avoiding mean-spirited interactions in games, and turning those moments into ones of shared joy.

This is at the heart of my objection to those framing in-game interactions as mean-spirited. It’s a failure to adopt the magic circle, the silent, implicit agreement of any shared gaming space.

This does not mean that interpersonal problems can’t occur at the game table. We shouldn’t be so naive. But we’ll talk below about why that can still happen, and why it generally involves some refusal – explicit or implicit – of the magic circle’s importance in creating compassionate gaming spaces.

Care Bears, Solo Gaming, and Positive Interaction

I’m going to throw some terms around (a few are mentioned in this section’s header), but it’s important to remember that judgment is absent here. These are trends, ones that we have to address to tackle this topic, but they aren’t used pejoratively.

If he didn’t invent the term, popular board game reviewer Rahdo (aka Richard Ham) certainly popularized the term “care bear” to describe himself – and eventually many others – as a gamer.

Basically, his preferences take him away from intensely interactive games. He doesn’t want direct or destructive interaction (stealing, attacking, lying, etc.), and tends to prefer games that have minimal interaction. In this context, “care bear” became a term to describe those that mostly want to be left alone in their gaming. They’ll compare scores at the end, see who did the best, and will enjoy this experience.

I actually really like Rahdo as a gaming media personality. He and I don’t share many game preferences, but he’s clear about what he likes and why, and is happy to admit when a game simply isn’t his style but without trashing the game in a general sense.

Solo gaming is another large recent trend in tabletop gaming. The pandemic supercharged this trend, and it hasn’t slowed down. A lot of gaming now happens alone.

This is all fine. Solo activities are a great way to enjoy yourself; some people read. Some people exercise. Some people play games on their own.

A final trend that coincides with a lot of this is that there are a lot of games trying to minimize antagonistic interaction and have everything be positive. The most obvious example is cooperative games, where everyone’s working together toward a common goal.

More games exist from the last few years that cater to these preferences, which I consider to be a good thing. No single style of gaming is for everyone, and it allows for a larger tent, so to speak, under which we can all enjoy games.

However, in any of these scenarios, there isn’t quite the same need to adopt the magic circle in the same way that we might need to for more punishing games. In and of itself, this again isn’t a bad thing. It’s just a different style of gaming.

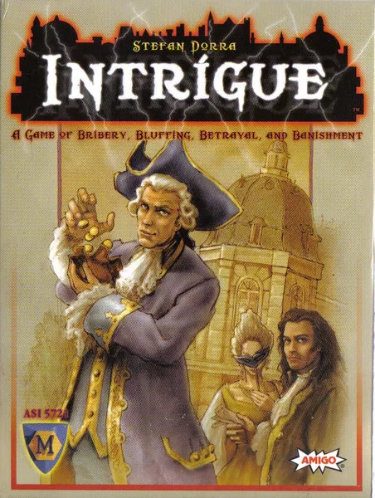

But what happens when this is your default method of interacting with games, and you’re suddenly asked to play an intense negotiation game that can – and probably will – include scheming, bluffing, and backstabbing?

Moreover, I’d even argue that more solitary games don’t actually necessitate much kindness and empathy during the course of the game. You largely leave each other alone, is all. It’s not as interpersonally demanding in some ways, which can be a boon depending on your mood. But you never really have to consider the other players in ways that more directly social games ask of you.

To those who are used to intense, cutthroat games, they might believe everyone is on board with the adopted premise and that no one’s at risk of feeling salty at the bad beats that will inevitably happen to some players. To them, they’re investing into the shared understanding and believe it’s all part of the fun for everyone.

But to the next player over, they may interpret that investment in the premise much differently. And you can start to see how this can create schisms at the table when everyone is not approaching the experience with the same embedded expectations.

If you don’t enjoy interactive games like that, that’s fine. This isn’t about gaming tastes. It’s about understanding the perspective of other players in order to minimize misunderstandings and erroneous and hurtful assumptions about their playing preferences and habits.

Take That, Mean Games, Bash the Leader, and Other Coded Language

This is the flip side of the coin, and each of the terms just above can be neutral and descriptive, or used pejoratively to try to make value judgements about the people who enjoy them. By now, it should be obvious that I dislike the latter usages.

For a while in my local club, for example, I started to lean into the term “mean” to describe games I liked. It helped me identify others who liked the same games I did.

This, to me, is a form of kindness. If we don’t like the same games, I wish you all the fun in the world, but it’s worth us having honest communication in order to stay at separate tables a lot of the time. Otherwise one or both of us will have a worse time.

However, I stopped using “mean” as a descriptor when I realized that people were interpreting this as me wanting to be mean to other people in games, as though I was only happy if others were being put down. Which is a vastly different reality, and one that I found uncomfortable, hurtful, and antithetical to how I view gaming experiences, including (and sometimes especially) in so-called mean games.

This isn’t everyone, for clarity, and I have some good friends who enjoy playing so-called mean games with me specifically because they know I won’t take anything personally and will enjoy even the harshest, most chaotic proceedings that go against me, and thus there’s a freedom for them to enjoy the experience. One friend who typically doesn’t like punishing games, when asked, even said at one point “I guess I like playing mean games with Mark,” and it was as high a compliment as I’ve received in gaming, because it spoke to the level of trust he has with me at the table.

Similarly, the largest betrayal I’ve ever experienced in a game was from a friend whose wedding I attended later that year. As I write this, I’m having dinner and drinks with him and his equally cutthroat-in-games wife next week. They’re loving people, full stop. The betrayal story still pops up years after the fact, though, but with an air of respect and mutual satisfaction at the drama we got to create collaboratively. This is an individual story, but speaks to a larger whole.

And it again goes back to an acceptance or ignorance of the magic circle, and conflating in-game actions with out-of-game intent. To some, wanting to steal from other players in a game that allows stealing is tantamount to being a worse person. Needless to say at this point, I strongly disagree, and we’ll even get into how I think it’s a kindness to adopt supposedly mean roles in games that facilitate such actions.

Now, if you don’t want those things in your games, by all means, run the other direction when they’re suggested or find a game everyone will be more likely to enjoy. The point, though, is that there’s a separation of gaming experience and the people behind it, one that I believe is necessary to understanding how gaming fuctions and facilitates experiences between people.

If gaming isn’t compassionate, kind, and in pursuit of facilitating memorable experiences for all players, I’m not interested in it. So how do we start to work toward that?

DMing in Dungeons & Dragons

I have shifted in my approach to gaming as an adult, and I believe this shift has been in the direction of compassion.

I largely credit Dungeons & Dragons for this shift.

See, I run a lot of sessions in D&D, and you can’t be an antagonistic DM (Dungeon Master) who wants to ruin the other players’ fun, or you soon won’t have play partners (or friends).

Not that I was ever like that, but there was a focus on competition and winning in my gaming that is sometimes a bit myopic. It’s about how you did, not what the game was like for everyone.

Running D&D, the table’s fun is your fun; or at least it is for me. And so my role became one of facilitating the fun of everyone, and this became a proxy for my own enjoyment. This is a better way for me to experience games, period. It’s more joyful and shared, which is what I want.

However, this doesn’t preclude in-game antagonism, and this is the other reason I’m citing D&D.

Because as the DM, I’m roleplaying a lot of different characters, but among them are the villains. And if there are no true stakes to the game – as in, the players can’t legitimately fail – then a lot of the drama and highest points of emotion and elation would cease to exist.

So I’m rooting for the players, but also have to directly antagonize them in-game in order to create the most memorable experience for everyone at the table. I also can’t shy away from the punitive elements in the game, or I’d cheapen their investment in the premise.

We all adopt the roleplaying version of the Magic Circle, of course, wherein character death or failure isn’t my fault, per se, as a DM, and is simply a natural – and potentially even enjoyable – part of the game, a game that needs meaningful stakes and challenge to reach its highest heights. As a result, no one wants their character to fail or die, but we’ve had enjoyable character deaths, because they’re dramatic and memorable in the way that great stories often are.

So that’s the key: we’re all invested in the premise, and expect others to be, up to and including honoring the stakes and consequences of failure, in order for everyone to have the most fun.

That line describes the mentality I think is sometimes lacking in gaming spaces, and to me is the most compassionate approach to our gaming, one that doesn’t have to pull in-game punches to avoid vitriol and negative feelings, and indeed often leans into them to get the most from the game for everyone.

The Genuine Kindness of Antagonism

So with that mentality in mind at the board gaming table, I’ll often try to model the type of Magic Circle acceptance that I want to see more of, and which I believe creates the most trusting and entertaining environment.

I’ll play the villain, so to speak, to model certain mechanics, but then I’ll laugh and congratulate players when I get my comeuppance later in the game. It’s only play, in the childlike, innocent sense of that word. This is how I’ve been able to curate some of my gaming circles, and it’s done wonders for my enjoyment of games. We trust one another because we’re playing together.

Properly calibrated groups can take this to even higher levels. Some of the closest friendships I have through gaming have happened because we shared an antagonistic experience that was hilarious, heartbreaking (in a good way), and memorable in ways that showed us something about the other person. Not that they like punishing other people, but that they can approach any game with a playful, light-hearted mentality and have the ability to separate in-game actions from the personalities driving them.

These are some of the most kind, emotionally mature people I know, and I trust them not to do things that would deliberately harm someone’s gaming experience.

Culture Wars, Misunderstandings, and Why We Demonize The Other

But what about situations where there really is some sort of funk permeating the table due to a particular player? We have all been in such a situation.

This is a player issue that goes beyond the game, simply put, and either comes from them not adopting the magic circle, or having expectations and goals in a game that have nothing to do with the wellbeing of others.

I have played with people who want to win above all else, and will spend excessive amounts of time to make that happen, to the obvious detriment of the fun of others at the table. These people suck. I’ve also played with people who will deliberately target someone to try to piss them off. These people also suck.

They’re also breaching interpersonal rules of basic human etiquette that go beyond the trappings of the game. These people will find ways to make many shared experiences worse, not just board games. In these instances, it’s the person, not the medium, that needs adjustment.

There really are people who derive pleasure from the misery of others. And we have all shared game tables with them. Let us not delude ourselves. However, certain games do not point to this flaw. They may reveal this flaw and give such people an outlet for this trait. But we shouldn’t paint with too broad a brush in labeling all fans of certain games in a negative way. This is wrong.

There’s a common line about “needs the right group” for many games. While true, I think some don’t realize just how true it is. To get the most out of a game, you usually need people who enjoy that type of game; but you also need those who are at the same level of maturity and mutual trust so that no one feels nervous about in-game actions having real consequences. This is not only possible, to me it’s the healthiest way to approach games.

Poor interpersonal behavior is also not relegated to interactive games, for clarity. There’s a breach of etiquette, for example, when a gamer who really wants to play a new 3-hour game they just bought pitches it under slightly false pretenses and ends up roping gamers into an experience they’re not going to enjoy, simply because they want to get it played.

That game might be the most positive, least antagonistic game in existence, but that’s a bigger breach of interpersonal trust than anything that’s ever happened to me in a cutthroat board or roleplaying game.

That is not a hypothetical scenario. It’s one pulled from my own life.

However, I’m not going to use that anecdote – which I’ve unfortunately seen happen on several occasions – as indicative of an entire swath of gamers who play those sorts of games. By and large, gamers are a jovial, kind bunch. This is true of those who don’t like the same toys as me. But those individuals who prioritize their own interests over those of the group are not as kind as many friends I have who have happily punished me in innumerable games.

My point is that using game mechanics as a proxy for emotional intelligence, compassion, kindness, and other virtues is the wrong metric.

Because again, if you don’t like punishing games, that’s your prerogative. Personality type certainly plays into these sorts of preferences, and no game is going to appeal to everyone. My only point is that we need to distance ourselves from these preferences as indicative of deeper personality traits that are not related, and the false and harmful connections that can be made as a result.

Interests as a proxy for some virtue is nothing new in hobby involvement, unfortunately. We also occasionally see the conflation of a deep interest in heavy board games with general intelligence, which is both shamefully elitist and incorrect.

Conflation of interest with identity (i.e. “I like these things, therefore they represent something positive about the people who like them and/or they’re better than the alternative”) is a larger issue in several industry and hobbyist spaces (and online spaces generally), one beyond the confines of this article to cover fully, but we see examples of it manifesting in this way.

This again isn’t the majority of gamers, though, and so we shouldn’t use the bad apples as indicative of the whole. Which is one of my overarching points about any of this.

Toward Maturity and True Compassion in Gaming

This stuff isn’t easy, because a lot of times we’re sitting down at tables with people we barely know and are expected to trust that they have an approach toward gaming that is compatible with our own.

I’ve often found, though, that setting my own mentality properly smooths over a lot of this. We have our words, after all. E.G. “So we’re going to be fighting over these districts, and there will be times when you have to really stick it to someone to do whatever’s best for you. It’s gonna hurt! I hope to have that target on my back at some point, and look forward to exchanging cutthroat actions with you all. I’ll shake my fist like I’m angry, but I’m excited for that stuff too. If we’re all expecting some swings, it’ll be something that can be a lot of fun!”

Literally, I’ve said stuff like that before a lot of games while I’m teaching them. It’s setting expectations for the type of game we’re about to play so that no one’s caught off guard, and it’s an explicit statement that there’s no true vitriol here if we truly step into the game’s world with the right mindset. It’s outlining the particular circle we’re stepping into, to make sure there’s mutual agreement.

To go back to my example of DMing in D&D, it’s a directly opposed mechanical role – as with any interactive board game – but true compassion necessitates some in-game antagonism. Lots of it, in fact. But it adopts the other players’ fun as your own, and it’s a mindset that understands the nature of the experience, which then gives deeper meaning to the interactions you all take part in.

This is true kindness in games. Understanding that the table’s fun can enhance your own, and curating your presence at the table to maximize this in any situation. Kindness is not avoiding mean actions, unless the reason for that mean action is unrelated to the in-game experience, which means you haven’t stepped into the Magic Circle and we’re back to it being an interpersonal problem.

If you can’t tell, this is something I’m passionate about, because it’s a core part of what I consider to be my identity. No, not the games I like, nor even that I’m a tabletop gamer. But that I approach social situations hoping to be a part of something shared that we’re all contributing to, and that I try to create mutual investment toward everyone’s enjoyment.

To be called mean, or callous, or any number of other pejoratives due to a game preference is both false and hurtful, and it worries me to see such divides being created in online discourse, which then can bleed into in-person settings.

It’s indicative of larger tribal issues I think exist in online spaces, ones far darker and more damaging than board game labels. But as a small symptom that I can speak directly to, I think it’s worth acknowledging and combatting through both words and actions that affirm our approaches to modern gaming, and the value we place in its human context.

…

Like my content and want more? Check out my other reviews and game musings!

Read More From BTD

Recent Posts

Categories

- All (355)

- Announcements (4)

- Board Games (206)

- DMing (28)

- Game Design (17)

- Playing TTRPGs (22)

- Reviews (192)

- RPGs (142)

- Session Reports (91)

- Why Games Matter (9)